Teardown Fail & Salvage Win: When Hardware Dies Young

The “Two-Month” Curse

This device landed on my desk courtesy of a coworker. It had been working fine for her for about two months before it suddenly quit. Interestingly enough, this matches the exact lifespan experienced by another coworker with the same model.

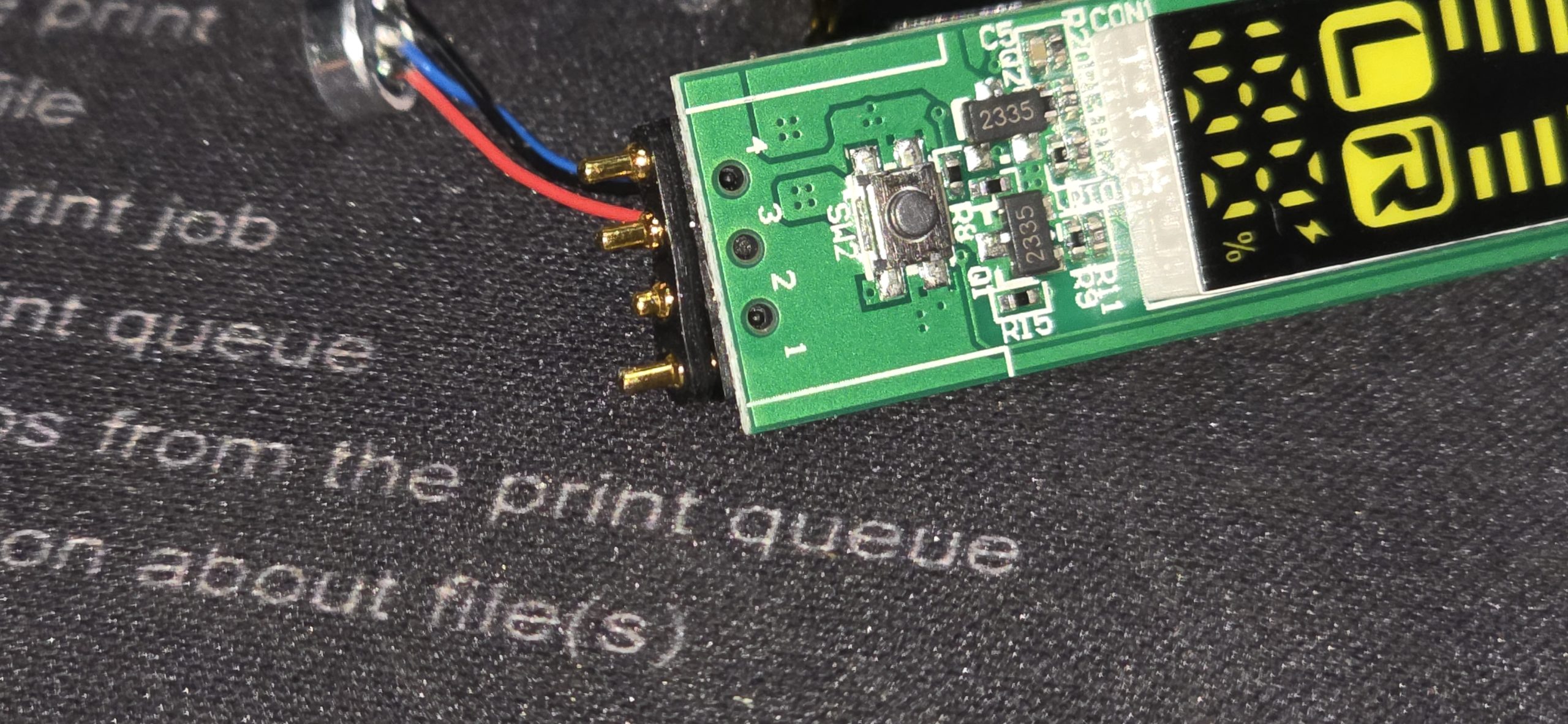

The culprit in both cases? A defective pogo pin.

In these devices, spring-loaded pogo pins are used to bridge the connection to the internal heating element. It seems that after a couple of months of use, these pins are prone to failure—likely getting stuck in the compressed position or losing their spring tension entirely. The result is a device that is fully charged but refuses to fire.

Since the device was already “bricked,” I decided to crack it open to see if I could unstick the pin or bypass it.

The Teardown (and the Meltdown)

These units are sealed tight so they aren’t meant to be serviced. To get inside, I had to apply heat to soften the casing. Unfortunately, the plastic housing had a much lower melting point than I anticipated.

The moment the plastic warped, the project shifted from “Repair” to “Salvage.”

The Prize: A Healthy LiPo Battery

Once the melted casing was out of the way, I stripped down the electronics. Even though the device had seen two months of use, the lithium polymer (LiPo) battery appeared to be in great shape.

Testing and Repurposing

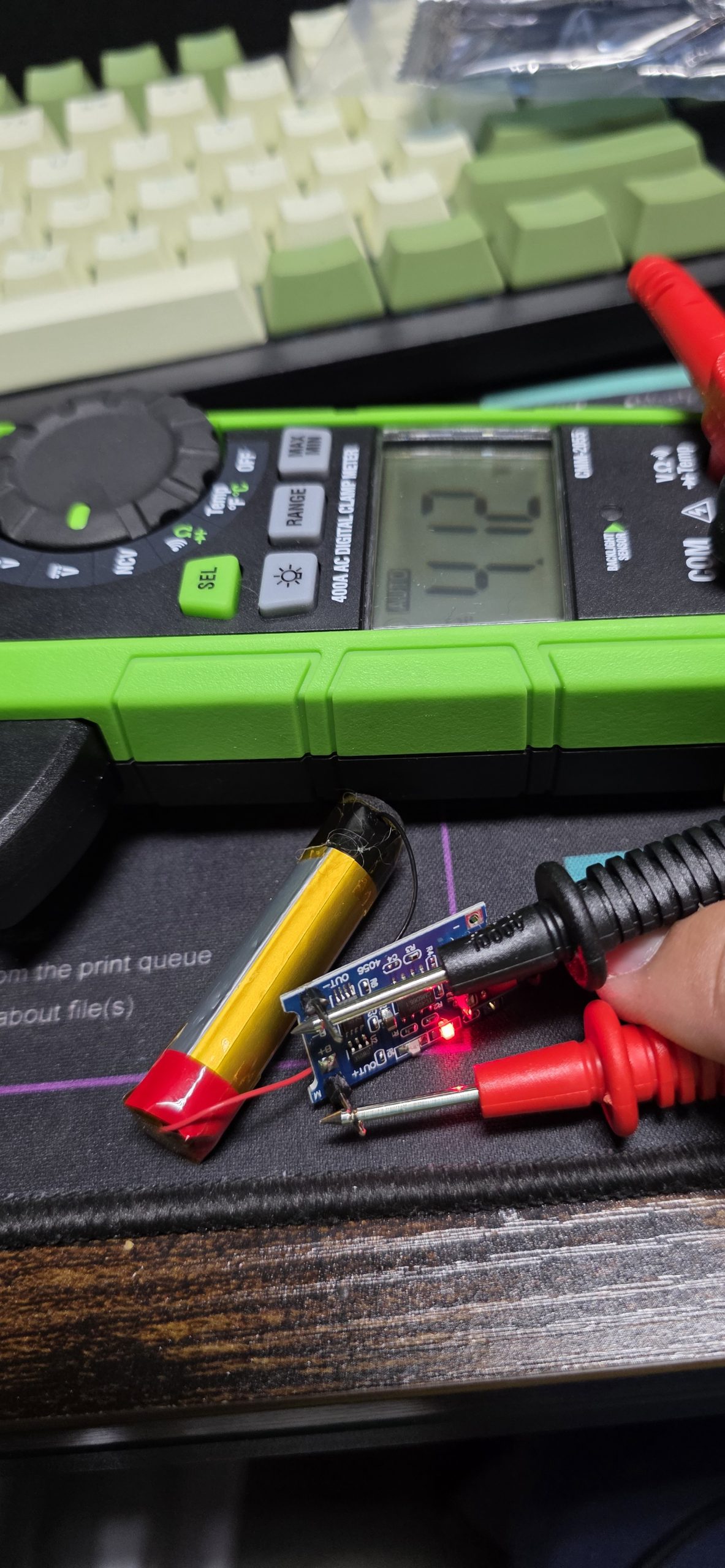

A naked battery is dangerous if you don’t know its state. I hooked the salvaged cell up to a TP4056 charging module to safely top it up and test the capacity.

The results were surprisingly good.

- Voltage Check: The multimeter read a healthy 4.12V.

- Capacity Test: Charging from dead, the battery took in 698 mAh—actually exceeding its printed rating of 650 mAh.

To verify this wasn’t just a fluke, I put it to work in the real world. I rigged it up to power an ESP32 microcontroller running a small OLED screen and an AHT10 temperature/humidity sensor. This is a relatively power-hungry setup compared to a simple sensor node.

The result: It ran the ESP32 setup continuously for over 8 hours.

Conclusion

While I couldn’t fix the device for my coworker (the melted plastic sealed its fate), the autopsy confirmed that the failure point was the mechanical contacts giving out prematurely.

It is frustrating to see a battery that tests above its rated capacity—capable of driving an ESP32 project for a full work day—destined for the landfill because a cheap metal spring failed after 60 days. At least now, this specific battery has a second life in my lab.

Leave a Reply